- Home

- David W. Brown

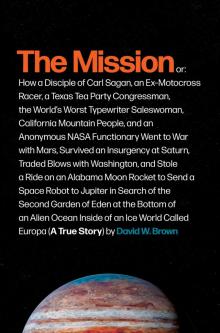

The Mission

The Mission Read online

or: How a Disciple of Carl Sagan, an Ex–Motocross Racer, a Texas Tea Party Congressman, the World’s Worst Typewriter Saleswoman, California Mountain People, and an Anonymous NASA Functionary Went to War with Mars, Survived an Insurgency at Saturn, Traded Blows with Washington, and Stole a Ride on an Alabama Moon Rocket to Send a Space Robot to Jupiter in Search of the Second Garden of Eden at the Bottom of an Alien Ocean Inside of an Ice World Called Europa (A True Story)

Dedication

TO MY MOM,

the first reader I ever knew

Epigraph

Beware, Diomedês! Forbear, Diomedês!

Do not try to put yourself on a level with the gods;

that is too high for a man’s ambition.

—ILIAD

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Dramatis Personæ

Chapter 1: The Course of Icy Moons

Chapter 2: Situations Vacant

Chapter 3: The Dark Ages

Chapter 4: The Center of the Universe

Chapter 5: Station

Chapter 6: Maestro

Chapter 7: The Death Star

Chapter 8: Auto-da-fé

Chapter 9: Grand Theft Orbiter

Chapter 10: This Earth of Majesty, This Seat of Mars

Chapter 11: E Pur Si Muove

Chapter 12: The Baltimore Gun Club

Chapter 13: Clipper

Chapter 14: Princess-Who-Can-Defend-Herself

Chapter 15: Ocean Rising

Chapter 16: Train Driver

Chapter 17: Step Forward, Tin Man

Chapter 18: One Inch from Earth

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Photo Section

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dramatis Personæ

Robert Pappalardo, a planetary scientist

Louise Prockter, a geomorphologist

Galileo, a spacecraft orbiting Jupiter from 1995 to 2003

Carl Sagan, an astrophysicist

Viking 1 }

Two Mars probes, 1976 to 1982

Viking 2

Edward Weiler, the head of NASA science missions

Curt Niebur, a program scientist at NASA headquarters

Karla Clark, an engineer at Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Wernher von Braun, a rocket scientist

Daniel Goldin, the NASA administrator from 1992 to 2001

Pathfinder, a Mars rover mission in 1997

James Green, the head of planetary science at NASA

Fran Bagenal, a planetary scientist

Ralph Lorenz, a planetary scientist

Jonathan Lunine, a planetary scientist

Huygens, a probe that landed on Titan in 2004

Cassini, a spacecraft orbiting Saturn from 2004 to 2017

Susan Niebur, an astrophysicist

John Culberson, a U.S. congressman from Texas

Todd May, a materials engineer

Alan Stern, a planetary scientist and NASA science missions lead

MESSENGER, a spacecraft orbiting Mercury from 2011 to 2015

Mike Griffin, the NASA administrator from 2005 to 2009

Don Blankenship, a geophysicist

Ron Greeley, a geologist

Cynthia Greeley, a historian

Europa Orbiter, a spacecraft that never was, in 1999

JIMO, a Europa nuclear spacecraft that never was, in 2003

Europa Explorer, a spacecraft that never was, in 2007

Jupiter Europa Orbiter, a spacecraft that almost was, in 2010

Europa Clipper, a spacecraft that will orbit Jupiter

Mars Science Laboratory, a rover mission in 2012

Tom Gavin, an engineer

Dave Senske, a planetary scientist

Spirit }

Two Mars rovers, landed in 2004

Opportunity

Lori Garver, the deputy administrator of NASA from 2009 to 2013

Joan Salute, a program executive at NASA headquarters

Barry Goldstein, an engineer

Brian Cooke, an engineer

Chapter 1

The Course of Icy Moons

IT WASN’T ENOUGH TO MAKE THE STYROFOAM SOLAR system over his bed. The boy needed toothpicks, too, for the moons, and he pressed them into each planet, none for Mercury or Venus, one for Earth, two for Mars. He puzzled over Jupiter, the dozen discovered being too many toothpicks, so he accounted only for the four found by Galileo in 1610. The moons were made of crumpled masking tape, which he skewered and placed into orbit. And while little Europa wasn’t labeled or anything, it was with young Robert Pappalardo even then, on a two-inch wooden spike in a foam world of orange and red.

In 1970 Robert’s dad packed the clan Pappalardo into the family car and steered south to Virginia, one long, continuous drive from Jericho, New York, on the north shore of Long Island, west through the city and then down along the coast. The trip ended on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, which intersected the “path of totality” of a solar eclipse, the reason for the excursion. A total eclipse. A TOTAL SOLAR ECLIPSE. The sun blocked by the moon but for phantasmal arms of a shimmering corona, a black hole ripped in the daytime sky like some portal to another dimension, day turned to night for minutes and animals going crazy because what the hell is going on up there?—but across only a spaghetti strand of the United States, everywhere not in the path experiencing a miserable and pathetic partial eclipse, the moon taking a bite from the sun but nothing else, the animals not even noticing.

Anyway and either way, he didn’t get that lesson, young Robert, five at the time and not yet of the toothpick moons, the sedan seating only so many, and at some point, Bob—we’re sorry, really, and we’ll make it up to you—we’ve got to make a cut and, Bob, look, you would miss an awful lot of school for this trip and you love staying at your grandparents’ so what do you say? We’ll catch the next one? OK? OK.

Thirty-four years later, he thought of that, the eclipse, the craft store solar system, the masking tape Europa, when they offered him the moon from the ninth floor of NASA headquarters. Europa. It was discreet, but it was an offer. It happened between meetings on October 22, 2004. He was there that day on loan from the University of Colorado, where he was an assistant professor, to advise the agency on JIMO—the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter—and what could be achieved from further expeditions to the Jovian worlds. Pappalardo was part of the mission’s science definition team, an ad hoc group of scientists who kneaded the knowns and knowledge gaps of a celestial object or system and determined the scientific objectives that should thus drive a prospective mission there. The simple ability to go somewhere started conversations, but before the National Aeronautics and Space Administration would pay engineers to spark blowtorches and build spaceships, there had to be a reason, some overriding and scientifically compelling purpose beyond Because It’s There.

The Jupiter system was the destination, but Europa was the goal, the target, the quarry. Beneath the frozen moon’s granite-hard ice shell was a liquid saltwater ocean, long hypothesized1 but at last discovered by physicists at the University of California, Los Angeles.2 If life existed anywhere else in the solar system, it was in that water—and not fossilized microbes like they scratched and sniffed for fruitlessly (and relentlessly) on Mars, but conceivably complex life—fish!—and few causes could be more compelling.

Still, no way it would ever fly, JIMO.3 Bob knew that. It was too big, too expensive. Bob had been part of previous Europa mission studies far more feasible, financially and technologically, that died ultimately and unceremoniously in agency filing cabinets. JIMO would have been a thrilling,

monumental mission, certainly—would have transformed not only Europan science, but the very nature of planetary exploration itself—but something so big needed the sort of sustained support unlikely to last long, and the probability of a pulled plug was why a manager from Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA’s research and development center in Pasadena, California, pulled him aside.4

Bob, began the furtive conversation, I hear that maybe you’re not satisfied teaching.5

WHEN PAPPALARDO WAS a child, astronauts worked and played on the moon. It was just normal, a thing people did, like work in a factory, bank, or bakery. They set up seismometers. They collected rocks. They explored this strange new world and encountered mystifying phenomena: spots of orange dirt on its plaster landscape, jarring flashes of light when they closed their eyes. Scientists on Earth solved these puzzles: the former formed by fire fountains in Luna’s primordial past;6 the latter, cosmic rays colliding with retinas.7 Astronauts drove cars up there. They played golf. They brought mice with them. Pets! In space!

Bob was never going to be an astronaut—that just wasn’t in the cards—but he was a child of Star Trek, and across five-year missions, Spock pointed the way in first run, and then in syndication, and then in animation (the Vulcan really drove the point home): science. During high school, Bob worked at Vanderbilt Planetarium in Centerport, Long Island, not far from his house. A few years later at Cornell University in Ithaca, he found the field of planetary science the way everyone else in the wider discipline did: through a Carl Sagan Moment. Upon enrolling, Bob had intended to take up the ancient art of astronomy, but problem the first: there was no astronomy major proper at Cornell; the field was taught under physics. Problem the second: physics. Bob therefore soon switched studies, his base camp now the university’s new geology building. Myriad mineralogy labs lined its hallways, and to study the stuff of the Earth was to spend long days and late nights in them, over big, binocular-type microscopes adorning tall black lab tables. Pappalardo was seated in one such lab on one such night behind one such microscope when another student, first name John, last name Berner, and so of course they called him Bunsen, walked in.

Hey, Bob, asked Bunsen. You know about this course Sagan is offering? This course on icy moons?8

Bob did not know about this course Sagan was offering, this course on icy moons, but he went home that night, pulled out the course catalog, and looked it up. ICES AND OCEANS IN THE OUTER SOLAR SYSTEM. Instructor: SAGAN, CARL.

That Carl Sagan, yes. He of Cornell, yes, of course. The prominent professor was for Bob part of the university’s initial allure, but Sagan didn’t always teach, had a lot going on. Carl Sagan, recently of Cosmos (book and television series) and The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson (television series). Carl Sagan, of the NASA spacecraft Voyager 1 and 2, the robotic explorers that in 1979 transformed the four telescopic dots of Jupiter’s moons into jaw-dropping globes of fire and ice, and later, around Saturn, revealed worlds diverse, living, geologically active, almost fully-fledged and practically planets (further study needed). Carl Sagan of the spacecraft Viking 1 and 2, which in 1976 revealed the Martian surface to be barren, though certainly in possession of everything necessary for life to exist (further study needed). Carl Sagan, a superstar in a profession bereft even of minor celebrities, who brought astrophysics into blue-collar living rooms, who in turtlenecks and with windswept hair spoke like a philosopher, practically in verse, and presented the pursuit of knowledge as something intrinsic and vital to the soul of every human being. Carl Sagan, who used his platform and lilting baritone to advance social causes, who planned protests against nuclear weapons test sites, arms linked with fellow activists, who crossed police lines and was placed gladly under arrest—Armageddon’s Thoreau—in order to advance the cause. Page one the next day: a rebel astronomer in handcuffs! Carl Sagan, with a Ph.D. behind his name and a childlike imagination inside his head, who had, for example, lobbied for a light to be added to the Viking lander so that at night Martian animals might be attracted to it and scurry up to investigate.9 Well, why not? Nobody knew what waited on the surface of the Red Planet.

That Carl Sagan.

It was a graduate-level course. Bob the undergrad had to request permission, and Carl the professor had to grant it. Bob did. Carl did. The peculiar part of taking a celebrity scientist’s class, Bob soon learned, was that you began to see him as a standard-issue human being. There is Carl Sagan with a coffee stain on his shirt. There is Carl Sagan making a caustic and callous remark about the student operating the slide projector. There is Carl Sagan being boring, writing another excruciating equation on the blackboard. There is Carl Sagan, exemplary but ordinary teacher, whose class, unbeknownst to Bob, would change the trajectory of his (i.e., Bob’s) life. It was in that classroom—conventional inventory: desks, blackboard, snapped chalk, and tile flooring—that Bob first learned about the most mesmerizing moon revealed by the two spacecraft Voyager: the world Europa, this icy-blue eyeball circling Jupiter, etched mysteriously with crazy brown scratches. Some speculated that an ocean might exist beneath all that ice—the physics suggested it—but, again, more study was needed.

Bob completed his bachelor of arts at Cornell and pursued a graduate degree at Arizona State University. He hit a wall there, however, and left before completing his master’s in geology. The 105-degree summers didn’t help, the Tempe sun so severe, so low in the sky that you could almost reach your arm into it—how he hated Arizona, and the conservatism of the place, and the corrupt governor Evan Mecham, who was just thoroughly reprehensible: canceling the state’s paid Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday, defending the use of racial slurs. (Bob had even worked on the Mecham recall, though the governor was impeached for, and convicted of, obstruction of justice and misusing government funds, and removed from office before voters could do it themselves.) Bob had friends in the simmering state, of course, followed local bands and played guitar at open mic nights and sang Dylan and the Dead, but graduate school was just dispiriting, basically hopeless, and with little promise of hope ahead. He realized a little too late in his program that his master’s thesis was overly aggressive in scope and that he would never be able to finish it. His graduate advisor, recognizing a lost cause, seemed to have moved on. So when Bob learned from a friend about a one-year internship at Vanderbilt Planetarium, where he had worked in high school, he applied and was hired. A one-year sabbatical from school—that was the plan—it would be a kind of collegiate convalescence—but maybe he was just finished with the enterprise entirely and would never return.

He liked life at the planetarium, stepped right back into it, and he was teaching the stars to students who were captivated, eager to learn, and Bob talked daily in the dark to the backs of two hundred heads, and it was rewarding, worthwhile work. That master’s had just stretched on and on and on, and he looked at what he was doing now, and maybe he didn’t need graduate school after all.

The internship paid ten thousand dollars, which stretched just enough to cover rent for a moldy basement apartment on Jackson Avenue, a little dead-end street in Huntington, and not far from his new job. He shared said quarters with a Vietnam vet who would sometimes have his homeless friends over to sleep on the floor. The substandard accommodations were worth it because Bob enjoyed what he was doing, and the joy increased with each passing week and month. Only twelve of those months were funded, however, and after enough pages from the calendar fell to the floor, a grim reality set in: Bob was running out of time.

Then one day, while he was practicing at the planetarium dome console for the next show, the phone rang. He answered.

Bob, said the voice, how would you like to come back?10

It was Ron Greeley, his graduate advisor and mentor at ASU.

Before that call, Bob had felt that maybe Ron had given up on him. It’s part of what made the planetarium job such a relief: that lack of disappointment looming gloomily from above. Ron was a professional, a professor’s professor, a founding father of th

e field of planetary science, and was above all a soft-spoken gentleman. But you felt his disapproval. The call was evidence that maybe Ron still believed, still saw potential in wayward Bob. It was just so nice. Bob’s thing, his gift, his curse at the time, was that he saw details—so many details—and his mind adamantly insisted on assembling those details into a big picture, a coherent story. Ron picked up on this, said a master’s thesis was just too small to contain what Bob had been doing. And Ron was right. It should have been easy, and yet it was taking years. So the student and the professor had the conversation, and not long after, Bob went back to Arizona, which was still an awful place, and the two of them turned his master’s thesis into a doctoral dissertation. Dr. Pappalardo crossed the stage in 1994.

After a lengthy postdoctoral research position, Bob found a job as an assistant professor of planetary science in Boulder, Colorado, in 2001. The singular focus of his professional life had been the evolution and activities of “icy moons”—the frozen satellites circling Saturn and Jupiter and Uranus and Neptune, those planets so large as to host planetary systems of their own, in miniature. That’s what he studied, that’s what he taught.

But was he satisfied teaching? he was asked that day on the ninth floor of NASA headquarters.

He was, but maybe he wasn’t. He was a good instructor, he thought. He liked the university and he loved living in Lyons, just north of Boulder, along the foothills, and lying in his hammock on the front porch, watching the sun sink behind Longs Peak—what climbers called the “flat-topped monarch” of Rocky Mountain National Park.11 He had a girlfriend. He had a cat. He contra danced—Boulder was great for that because you could drive north to Fort Collins or south to Denver, both with thriving communities of light-footed locals—hands four from the top, gents on the left, ladies on the right, face your partner, do-si-do—and every weekend, he’d strap on his Volkswagen Passat, this silver thing, custom plates (ICY SATS)—a little too much car, he thought, but he had the cold weather package and it was fine, and he had snow tires—and he’d drive north or south to swing his partner round and round.

The Mission

The Mission